고혈압의 진단 및 치료: 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인을 기반으로

Recent Update on Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension: Based on the 2023 European Society of Hypertension Guidelines

Article information

Trans Abstract

Since the release of the updated hypertension guidelines by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension, noteworthy revisions have been introduced by both the Korean Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Hypertension. Given the increasing prevalence of hypertension, it is essential for neurologists who frequently encounter patients with multiple chronic condition to have a thorough understanding of hypertension. In addition, effectively controlling hypertension can potentially lower the risk of neurological disorders including stroke and cognitive impairment. Thus, it’s crucial for neurologists and healthcare professionals to possess a comprehensive understanding of diagnosing and managing hypertension. Therefore, in this paper, the essentials for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension based on the latest guidelines from the European Society of Hypertension are summarized.

서 론

고혈압은 우리나라 성인 인구 3명 중 1명인 1,200만 명이 보유한 대표적인 국민 만성 질환이다[1]. 고혈압은 성인의 사망 원인 중 가장 주요한 위험 요인인 심뇌혈관질환과 밀접한 관련이 있고 적절히 치료가 된다면 그로 인한 심뇌혈관 합병증 및 사망 위험을 감소시킬 수 있는 조절 가능한 위험인자라는 점에서 중요하다[2]. 국내의 고혈압 조절률은 빠른 추세로 상승 중이나 유병률은 여전히 증가 추세이며 고혈압 환자의 경우 뇌졸중 및 인지장애 등의 신경계질환을 동반하는 경우가 많으므로 신경과 의료진의 고혈압 진단 및 관리에 대한 숙지가 필요하다[3,4]. 2022년 대한고혈압학회에서 국내 실정에 맞는 고혈압 진단 및 치료지침을 발표하였으며 이후 2023년 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인이 개정되었다. 본 논문에서는 2023년 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인 개정안을 중심으로 국내 성인에서의 정확한 고혈압 진단 및 적절한 치료에 대하여 살펴보고자 한다[5,6].

본 문

1. 고혈압의 정의

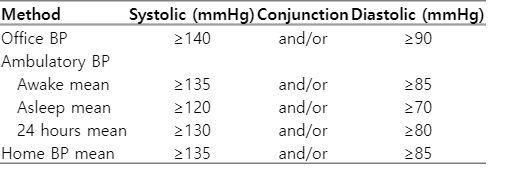

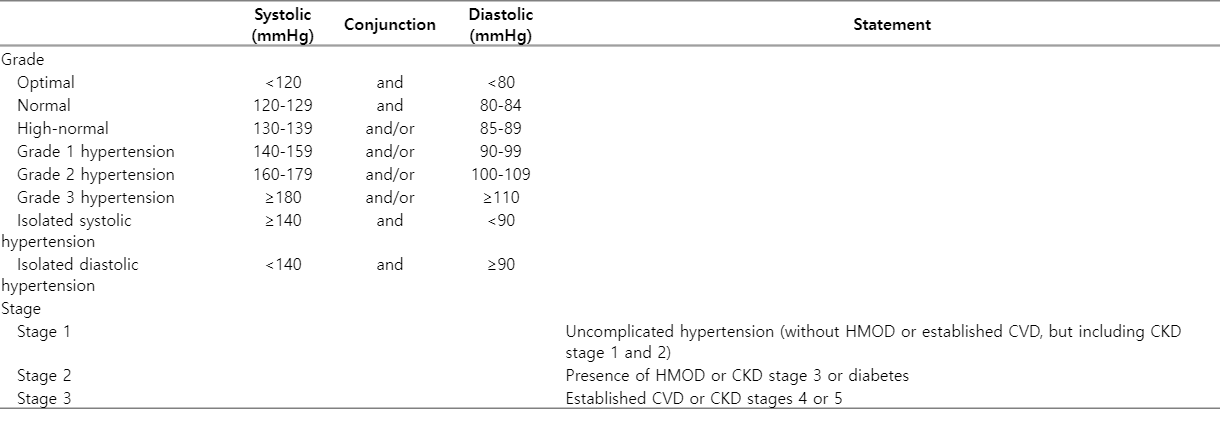

현재까지의 심뇌혈관질환 예방에 관한 임상 연구 결과를 바탕으로 140/90 mmHg 이상을 고혈압이라고 국제적으로 정의하고 있다(Table 1) [2,7,8]. 정상 혈압은 수축기혈압 120 mmHg 미만이면서 확장기혈압 80 mmHg를 모두 만족하는 경우를 뜻하며 임상적으로 심뇌혈관 위험도가 낮은 혈압군이라는 의미를 갖는다. 2017년 미국고혈압학회 진료지침에서 고혈압을 130/80 mmHg 이상으로 정의하면서 고혈압 정의에 대한 논란이 있었으나 미국심장폐색전연구원의 고혈압 가이드라인인 Joint National Committee 7 가이드라인, 2022 대한고혈압학회 진료지침 및 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인의 경우 기존의 140/90 mmHg 이상을 고혈압으로 정의하는 기준을 유지하고 있다[5,6,9,10]. 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서는 고혈압의 정의에는 변화가 없으나 혈압 수치에 근거하여 고혈압의 등급(grade)을 나누고 고혈압 연관 장기 손상을 고려한 단계(stage)를 구분하여 용어를 정리하였다(Table 2, Fig. 1). 고혈압 단계의 상세 기준과 의미에 대하여는 하기 고혈압 환자의 평가에서 서술하였다.

Indicators of hypertension-mediated organ damage. Adapted from Mancia et al.6 Table 11. ECG; electrocardiogram, LVH; left ventricular hypertrophy, aVL; augmented vector left, LVM; left ventricular mass, BSA; body surface area, RWT; relative wall thickness, LV; left ventricle, LVDDiam; left ventricular diastolic diameter, LAV; left atrial volume, GLS; global longitudinal strain, eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate, UACR; urine albumin-creatinine ratio, RRI; renal resistive index, PP; pulse pressure, baPWV; brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, cfPWV; carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, IMT; imtima-media thickness, CAC; coronary artery calcium, ABI; ankle brachial pressure index, KWB; Keith-Wagener-Barker.

2. 혈압의 측정

고혈압의 진단, 치료, 예후 평가에 있어서 가장 근간이 되는 것은 정확한 혈압의 측정이다. 혈압은 측정 환경, 측정 기기, 측정 방법, 혈압 측정 조사원의 술기에 따라서 변동성이 크기 때문에 커프를 사용한 상완 자동 혈압계를 이용하여 표준적인 방법으로 반복 측정한 진료실 수축기혈압 ≥140 mmHg 또는 확장기혈압 ≥90 mmHg를 기준으로 삼으며 이 외에 활동혈압 측정 또는 가정혈압 측정을 부가적으로 시행하여 고혈압을 진단하고 분류한다[6,9,11,12]. 측정 방법에 따른 기준이 다른 점에 대한 숙지가 필요하다(Table 1). 최근 개발되어 널리 사용되는 스마트폰 및 소형 기기를 이용한 커프 없는 혈압계로 환자들의 진료실 밖 혈압 측정에 도움을 받고 있는 부분이 있으나 혈압의 진단에는 사용하지 않는 것을 권고하고 있다[13].

처음 병원에 방문하는 환자의 혈압을 측정할 때에는 양팔의 혈압을 모두 측정하며 다음에는 혈압 수치가 높은 팔에서 혈압을 측정한다. 1분 간격을 두고 적어도 2회 이상 혈압을 측정하는 것이 기본이며 부정맥이 있는 경우 3회 이상 측정하여 평균을 낸다[9]. 혈압을 측정할 때에는 등받이가 있는 의자에 등을 기대어 앉도록 하고 양발을 평지 위에 내리고 다리를 꼬지 말아야 하며 위팔은 심장 높이에 위치시켜야 한다. 최소한 5분간 안정된 상태를 취한 다음에 커프를 심장 높이에 위치시켜 혈압을 측정한다[11,14]. 커프는 팔 둘레에 적절한 커프를 사용하여야 하며 만약 적정 크기보다 작은 크기의 커프를 사용하여 측정하면 혈압이 높게 측정된다. 대부분의 커프에는 적용 가능한 팔 둘레의 범위가 표시되어 있어서 팔에 둘러보고 적합한지를 육안으로 확인하는 것도 도움이 되며 진료실에 3-4개 정도 사이즈의 커프를 구비하는 것이 다양한 연령대와 체형의 환자의 혈압을 측정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 수축기혈압 180 mmHg, 확장기혈압 110 mmHg 이상의 3도 고혈압 환자를 제외하면 고혈압을 진단하기 위해서는 상기 기술한 혈압의 표준 측정법을 사용하여 4주 이내 2회 이상의 외래 방문 시의 혈압 측정값을 사용하여 판단할 것이 권고된다.

진료실에서의 혈압 측정 외 활동혈압 측정 혹은 환자가 직접 시행할 수 있는 가정혈압 측정은 진료실에서 측정된 혈압보다 예후를 더 잘 반영한다고 알려져 있다[15-18]. 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서도 진료실 밖 혈압 측정의 중요성에 대하여 강조하고 있다. 가정혈압 측정은 검증된 자동 혈압계를 이용하여 위에 기술한 표준 혈압 측정법으로 2회 측정한다. 환자에게 아침 기상 후 1시간 이내, 소변을 본 후, 고혈압 약을 복용하기 전에 1회 측정하고 저녁 잠자리에 들기 전에 1회 측정하도록 시간에 대한 지침을 줄 수 있다. 가정혈압 측정을 통해 처음 고혈압을 진단할 때에는 적어도 외래 방문 전 7일은 꼭 혈압을 측정하도록 권고하고 최소 3일 이상의 측정은 반드시 필요하다. 가정혈압 측정은 필요 비용이 낮고 백의고혈압을 감별할 수 있으며 긴장되지 않는 상황에서 반복적으로 장기적 혈압 측정이 가능한 장점이 있으나 측정법에 대한 지침을 미리 교육하는 것이 필요하다[19,20].

활동혈압 측정 역시 가정혈압 측정과 유사하게 일상생활 상황을 반영하며 하루 동안 여러 번의 혈압 측정을 제공할 수 있는 장점이 있다. 또한 다양한 자세 및 환경에서 측정이 가능하며 일상적인 주간 활동 및 수면 중에도 혈압을 측정할 수 있다[11]. 검증된 자동 혈압계를 사용하여 24시간에 걸쳐 주간에는 15-30분, 야간에는 30-60분 간격으로 혈압을 측정하며 예상 측정 횟수의 최소 70% 이상의 혈압 측정을 하게 된다. 이를 통하여 24시간 평균 혈압을 측정할 수 있고 진료실에서의 혈압 측정으로 판명되지 않는 저항성 고혈압을 식별할 수 있으며 24시간 혈압 변동성 및 아침 혈압 증가, 야간 혈압 변동 정도 등의 특성을 정량화하여 심혈관질환의 예후와 사망률을 더 잘 예측할 수 있다[11,21-23]. 그러나 활동혈압 측정은 잦은 사용에는 적합하지 않고 필요 비용이 적지 않으며 일반 의료 기관에서 널리 이용하기에 어려움이 있고 수면 중에 일부 환자에게 불편을 줄 수 있다는 단점이 있다[11]. 이외 중요한 제한점으로는 임상 예후에 미치는 영향을 탐색하기 위한 선행 무작위 대조 연구가 없어 치료의 혈압 임계치와 목표가 수립되어 있지 못한 점이 있다. 백의 효과가 제거되는 점을 고려하여 활동 혈압은 진료실에서 측정된 혈압에 비해 낮다고 알려져 있으며 활동혈압으로 측정된 24시간 평균 수축기혈압이 130 mmHg 또는 확장기혈압이 80 mmHg가 진료실에서 측정된 혈압 140 mmHg 또는 90 mmHg에 각각 해당한다(Table 1) [24].

가정혈압 측정과 활동혈압 측정을 통하여 백의고혈압과 가면고혈압을 찾아낼 수 있는 임상적 특장점이 있으므로 1단계 고혈압 환자 혹은 고혈압에 가까운 정상 혈압 환자에게서 가정혈압 측정과 활동혈압 측정을 고려할 수 있다[11]. 또한 진료실에서의 혈압 측정 시 변동이 커서 고혈압 진단에 명확한 결정을 내리기 어려운 경우, 기립성 혹은 식후 저혈압이 의심되는 경우에 고려할 수 있다. 추가적으로 가정혈압 측정과 활동혈압 측정이 고려되어야 하는 사안으로는 혈압 변동성의 측정이 있다. 혈압은 하루 동안 매우 변동성이 높으며 특히 주간에는 그 변동이 큰데 24시간, 외래 방문 간 또는 장기적인 혈압 변동성이 24시간 평균 혈압과 독립적으로 심혈관 결과에 부정적으로 연관되어 있음이 진료실에서의 혈압 측정을 통해 알려져 있다[23,25]. 이에 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서는 혈압 변동성 측정의 중요성을 강조하고 있다. 치료 중인 고혈압 환자의 심혈관 위험을 보다 정확하게 평가하는 데 진료실에서의 혈압 측정뿐 아니라 혈압 변동성도 고려하는 것이 유용함을 임상의가 파악하고 치료를 받는 환자들에게서 변동 없이 일관성 있게 혈압을 조절하는 것이 중요함을 강조하여 교육하는 것이 필요하다.

3. 고혈압 환자의 평가

고혈압을 진단하고 평가하기 위해서는 첫째, 일차성과 이차성 고혈압을 감별하고 둘째, 고혈압의 중증도를 평가하며 셋째, 심뇌혈관질환의 위험인자와 생활 습관을 파악하고 마지막으로 심뇌혈관질환 유무와 치료에 영향을 줄 수 있는 동반질환 또는 무증상 장기 손상 유무를 확인해야 한다. 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서는 위에 서술된 고혈압의 등급과 단계의 개념을 도입하게 되었다.

고혈압 환자에서 평가를 위한 진찰 및 검사를 하는 것은 향후의 위험도에 차이가 있기 때문이다. 측정되는 혈압의 수치에 따라 등급(grade)은 변할 수 있지만 단계(stage)는 일반적으로 변하기 어렵다. 고혈압 환자는 다른 심뇌혈관질환 위험인자를 동반하는 경우가 많아 혈압 조절만으로 관련 위험을 조절하는 것이 충분하지 않으며 무증상 환자에서도 고혈압 연관 장기 손상이 많이 확인되고 있기 때문에 심뇌혈관 위험도 산출을 위해서는 반드시 중요 지표 스크리닝을 해야 한다고 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서 강조되고 있다[11]. 전에는 표적 장기 손상(end-organ damage) 등의 표현을 사용하였으나 최근에는 구조적/기능적, 대혈관/소혈관의 개념을 모두 포함하여 고혈압 연관 장기 손상(hypertension-mediated organ damage)이라는 표현으로 개정하였다(Fig. 1). 이렇게 평가된 고혈압의 등급과 단계에 따라 심뇌혈관 위험도를 계층화하였으며 Fig. 2에 제시된 바와 같이 유럽의 경우 SCORE2 혹은 SCORE2-OP 등의 개별 심뇌혈관 위험도 예측 도구가 있어 이를 기반으로 계층화 지도를 제시하였고 국내 환자를 대상으로 한 계층화 지도는 현재 개발 중이다[26,27]. 이러한 위험도 계층화 접근 전략은 특히 높은 정상 혈압 혹은 1도 고혈압 환자에서 고혈압 치료를 시작할지를 결정하는 중요한 근거가 된다. 고혈압 치료가 조기에 진행된다면 일부 고혈압 연관 장기 손상이 회복될 수 있기 때문이다[28]. 고혈압이 오래 지속될 경우 추후 치료를 통하여 혈압을 조절하더라도 고혈압 연관 장기 손상이 회복되지 않을 수 있다[28].

4. 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시작과 목표 혈압

고혈압 환자의 평가가 중요한 이유는 고혈압 치료를 시작하고자 할 때에는 제대로 측정된 혈압의 수치뿐 아니라 개개인의 기저 위험도를 고려하여야 하기 때문이다. 심뇌혈관질환이 없는 환자와 있는 환자의 치료 시작 시점은 다르다. 심뇌혈관질환의 위험도가 높은 환자일수록 같은 정도의 혈압을 떨어뜨릴 때 기대되는 이득이 높다고 알려져 있다[29].

고혈압 치료를 통하여 심뇌혈관질환을 예방하는 효과가 아무리 우수하여도 고혈압 전 단계에서 약물 치료는 권고하지 않는다. 혈압에 따른 심뇌혈관질환의 사망률은 115/75 mmHg에서 수축기혈압이 20 mmHg, 확장기혈압이 10 mmHg씩 증가함에 따라 2배씩 계속 증가한다[29]. 즉 혈압이 120/80 mmHg 이상인 경우에는 고혈압의 발생 및 심혈관 사건을 예방하기 위하여 적극적인 생활 요법을 권고하여야 한다[30,31]. 아직 고혈압 전 단계에서 조기 약물 치료의 효과는 명확하지 않다[31]. 다만 높은 정상 혈압 환자 중 고혈압의 단계가 높아 고위험 혹은 최고위험 그룹으로 평가되는 경우 치료 효과가 있다[32]. 심뇌혈관 위험도가 저위험군인 1도 고혈압인 경우 약물 치료를 시작하는 것에 대한 임상 근거가 다소 빈약하여 생활 요법을 먼저 시행한 후 조절되지 않을 때 약물 치료를 시작하도록 권고되며 심뇌혈관 위험도가 있는 1도 고혈압 혹은 고혈압의 등급이 2도 고혈압 이상일 경우 바로 약물 치료를 시작하도록 권고된다[29,33]. 다만 80세 이상의 고령 환자의 경우 수축기혈압이 160 mmHg 이상일 시 고혈압 치료를 고려할 수 있으며 이러한 결정은 환자 개인의 심뇌혈관 위험도 및 위약의 정도를 감안하여 개별적으로 접근해야 한다고 권고되고 있다.

일차적으로 혈압을 낮추기 위한 목적으로 항고혈압약을 복용한 환자에서 목표 혈압에 관한 연구로 strategy of blood pressure intervention in the elderly hypertensive patients (STEP) 및 action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes (ACCORD) 연구가 있으나 최근의 메타 분석에서는 심혈관질환이 없는 고위험군 환자를 140/90 mmHg 이상의 혈압에서 약물 치료를 시작하여 수축기혈압을 130 mmHg 가까이 낮추는 것이 심혈관질환에 대한 예방 효과가 가장 뛰어났기 때문에 심혈관질환이 없는 고위험군에 대하여 혈압을 130/80 mmHg까지 낮추도록 권고하였다[34]. 다만 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에는 목표 혈압의 상한선뿐만 아니라 하한선을 제시하여 고혈압 치료 시 무조건적으로 혈압을 낮추는 것이 아님을 강조하였다(Fig. 3). 또한 연령을 나누어 세부 목표 혈압을 제시하였는데 18-64세의 고혈압 환자는 목표 혈압을 130/80 mmHg 미만으로 제시하여 적극적 강압을 제시하였고 65-79세의 고혈압 환자는 목표 혈압을 140/80 mmHg 미만, 65-79세의 수축기 단독 고혈압 환자는 수축기혈압 140-150 mmHg, 80세 이상의 고령 환자의 경우 목표 수축기혈압이 140-150 mmHg이나 환자가 부작용이 없으면 130-139 mmHg까지 조절이 가능하다. 다만 수축기혈압이 70 mmHg 이하로 저하되는 상황은 주의하여야 한다는 세분화된 권고가 실려있다[35-37].

5. 고혈압의 약물 치료

2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서도 이전 가이드라인과 같이 기존에 가장 많이 사용되는 5대 계열 약제에 대한 소개는 유지되었다[38]. 5대 계열 약제는 안지오텐신전환효소억제제(angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors), 안지오텐신II수용체차단제(angiotension II receptor blockers), 칼슘통로차단제(calcium channel blockers), 싸이아자이드 또는 싸이아자이드 유사이뇨제(thiazide/thiazide-like diuretics), 베타차단제(beta blockers)이다. 기존 가이드라인과 다른 차이점은 베타차단제의 중요성이 부각된 점과 SGLT2억제제(sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors) 및 비스테로이드무기질코르티코이드길항제(nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) 등의 약제가 사용 가능하고 효과적인 계열로 추가된 점이 있다.

빠른 효과를 위하여 일차 치료 약제로 고령, 높은 정상 혈압, 1도의 저위험 고혈압 환자 외의 대부분의 환자에서 2제 병용 요법을 시작할 것이 권고되고 있으며 2제 요법 시 안지오텐신전환효소억제제/안지오텐신II수용체차단제 계열에 더하여 싸이아자이드 또는 싸이아자이드 유사이뇨제 계열 혹은 칼슘통로차단제 계열을 이용할 것을 추천하고 있다. 3제 요법의 경우 위에 언급한 3개 계열의 약제를 시작해 볼 수 있다(Fig. 4). 약제를 사용할 시에는 각 계열별 유의점을 사전에 숙지하여야 한다(Fig. 5).

Classes of antihypertensive drugs. Recommended combinations are indicated by the blue lines. ACEi; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB; angiotensin II receptor blockers, CCB; calcium channel blockers, BB; beta blockers.

Contraindications or precautions for antihypertensive drugs. Adapted from Mancia et al.[6] Table 15. ACEi; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB; angiotensin II receptor blockers, DHP-CCB; dihydropyridine-calcium channel blockers, HFrEF; heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, AV; atrioventricular, LV; left ventricle, LVEF; left ventricular ejection fraction, CKD; chronic kidney disease, MRA; mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate.

이전의 가이드라인에서는 다른 계열의 혈압 조절 약제들과 비교 시 베타차단제가 뇌졸중에 대한 위험도 감소 효과가 적은 점과 대사증후군 환자에서 신규 발생 당뇨병 빈도가 높았던 점이 약점이었으나 2023 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인에서는 급성/만성 관상동맥질환, 심근경색 후 부정맥, 협심증, 심부전, 심방세동, 임산부 및 임신 계획 시 등 특정 임상 상황에서 베타차단제가 유리한 효과가 있는 점이 제시되었다[39-41]. 다만 이러한 이점이 있음에도 천식, 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환, 2-3도 방실전도장애, 대사증후군 환자 및 노인 환자에게 투여 시 주의하여야 한다.

현재 항고혈압 약물 치료의 주축을 담당하는 계열은 안지오텐신전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신II수용체차단제로 혈압 강하 이외에도 심혈관 및 고혈압 연관 질환인 심근경색증, 심부전, 관상동맥질환, 당뇨병성 신증 및 만성 콩팥병 등에서 우수한 효과가 증명되어 현재 특별한 금기가 없는 한 고혈압 1차 약제로 널리 사용되고 있다[42,43]. 신장 보호 효과에도 불구하고 안지오텐신전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신II수용체차단제는 콩팥 기능을 약화시켜서 혈청 크레아티닌이 상승할 수 있으므로 투약 시 처음 1-2개월 내에 혈액 검사를 시행하여 크레아티닌이 30% 이상 상승하거나 혈중 칼륨이 5.5 mEq/L 이상 증가하는지에 대한 모니터링이 필요하다. 특히 만성 콩팥병 환자로 혈청 크레아티닌이 3.0 mg/dL 이상인 경우 고칼륨혈증의 발생에 주의해야 한다. 안지오텐신전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신II수용체차단제는 태아에 기형을 초래하는 것으로 알려져 있어서 임신부에게는 금기이며 임신이 예정되어 있거나 가임부에서는 투약 시 주의해야 한다.

레닌-안지오텐신-알도스테론계(renin angiotensin aldosterone system)의 마지막 단계에서 작용하는 비스테로이드무기질코르티코이드길항제(nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists)인 스피로놀락톤(spironolactone) 및 에플레레논(eplerenone)의 경우 심박출량감소 심부전(heart failure with reduced ejection fraction)에서 사용되나 혈압 강하 효과의 가능성 역시 제시되어 있다[44]. 또한 역시 안지오텐신계에 관여하는 약제로 안지오텐신수용체 억제제와 나트륨이뇨펩타이드를 분해하는 네프릴리신을 억제하는 약제의 병용 요법(angiotension receptor-neprylisin inhibitor, valsartan-sacubitril)이 소개되어 있다. 심부전 환자에서 승인된 약제이나 최근 메타 연구에서 기타 계열의 고혈압 약제에 비해 우월한 혈압의 저하 효과를 입증한 연구 결과가 제시되어 있어 새로운 혈압약 계열로 제시되고 있다[45].

칼슘통로차단제는 저렴한 약가, 안정적인 약동학적 성질과 우수한 임상 결과를 고려하여 현재까지 널리 사용되고 있다. Dihydropyridine 계열의 칼슘통로차단제인 암로디핀(amlodipine)은 심박출량감소심부전 환자 등에서 사용할 수 있다. Nondihydropyridine 계열의 칼슘통로차단제인 딜티아젬(diltiazem), 베라파밀(verapamil)은 혈관 비특이적인 특성이 있으나 혈압 강하 효과를 나타내며 항부정맥 약제로서의 효능이 동반되어 심방세동 환자에서 심박수 조절을 위해서 사용할 수 있다[2]. 칼슘통로차단제는 혈압 강하 이후에 반사적인 교감신경 활성화나 빈맥, 혈관 확장에 따른 다리 부종이 있을 수 있으므로 이를 잘 모니터링하는 것이 필요하다.

이뇨제의 경우 싸이아자이드형 이뇨제인 하이드로클로로싸이아자이드(hydrochlorothiazide)와 싸이아자이드 유사 이뇨제인 클로르탈리돈(chlorthalidone), 인다파미드(indapamide)가 사용되고 있다. 혈압 강하 측면에서는 싸이아자이드 유사이뇨제가 hydrochlorothiazide보다 효과가 큰 것으로 밝혀진 연구들이 있으나 심혈관계 사건 예방 효과에서는 hydrochlorothiazide와 chlorthalidone의 사용이 예후에 차이가 나지 않는 것으로 확인되었다[46-48]. 다만 사구체여과율이 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 미만인 경우 hydrochlorothiazide의 효과가 떨어지므로 이러한 경우에는 고리이뇨제가 추천되며 그럼에도 조절이 되지 않는 경우 chlorthalidone을 추가할 수 있다. 이뇨제는 저칼륨혈증, 저나트륨혈증, 고요산증, 혈당 증가, 고지혈증, 저마그네슘혈증, 고칼슘혈증 등 다양한 대사성 부작용을 유발할 수 있어 주의가 필요하다.

6. 신경계질환에서의 고혈압 관리

1) 뇌혈관질환과 고혈압

허혈 및 출혈뇌졸중 모두 혈압이 높을수록 위험도가 증가하며 고혈압은 조절 가능한 뇌졸중 위험인자 중에서 인구 집단에 대한 기여 위험도가 가장 높다는 점에서 중요하다[49,50]. 급성기 치료의 관점에서 보자면 혈종 확장, 혈종 주위의 부종, 재출혈과 뇌출혈 급성기의 혈압 상승이 연관되어 있기 때문에 뇌출혈 발병 후 6시간 이내의 환자들에게 혈압을 140/90 mmHg 미만으로 낮추는 것이 신경계 예후를 개선할 수 있다고 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인은 권고하고 있다[51,52]. 다만 미국의 뇌출혈 치료지침에서는 의학적 및 신경학적으로 안정된 환자의 경우 목표 혈압을 130/80 mmHg 미만으로 설정하는 것을 권고하고 있다[53,54]. 과도한 혈압 감소 효과에 대해서는 혈종 주위의 뇌허혈을 유발할 수 있어 주의가 필요하다. 급성기 뇌출혈에서 혈압 감소의 효과를 확인하기 위한 대표적인 두 임상시험인 INTERACT-2와 ATACH-II에 참여한 환자들의 메타 분석 연구에서 수축기혈압이 60 mmHg 이상 감소된 경우에는 더 불량한 예후를 보였다[55]. 뇌출혈 발병 후 6시간 이후에 치료를 시작하는 환자들의 경우 메타 분석 연구에서 혈종의 확장은 줄였으나 임상 예후의 회복에는 유의한 효과가 없었다[56]. 다만 초기 수축기혈압이 220 mmHg 이상일 경우 140-180 mmHg 아래로 수 시간에 걸쳐 천천히 조절하는 것이 추천된다[57,58].

급성기 허혈뇌졸중의 경우 대부분의 환자들에서 초기 혈압 수치가 높으며 발병 후 48-72시간 동안 자연적으로 점진적 감소를 보인다[59]. 허혈뇌졸중 후 72시간 동안 혈압이 220/120 mmHg 이하인 경우 혈압 감소의 효과가 일관성 있게 보고되지 않았기 때문에 혈압 감소 치료를 자제하여야 한다. 다만 혈전용해제 투여나 혈전제거술와 같은 재관류 시술을 받거나 받을 환자들은 혈압이 현저하게 높을 경우 뇌출혈 위험이 증가한다는 관측적 연구 결과가 있으므로 이러한 환자들에서는 초기 혈압 조절이 필요하다. 혈전용해제 투여 환자의 경우 투여 전 혈압을 면밀히 모니터링하고 관리하여 목표 혈압인 <180/110 mmHg 이하로 유지하여야 하며 만약 환자의 혈압이 이보다 높다면 항고혈압 약물을 사용하여 목표 범위로 혈압을 낮춘 후 혈전용해제를 투여하여야 한다[60]. 투약 이후 혈압을 최소한 시술 후 첫 24시간 동안 180/105 mmHg 이하로 유지하는 것이 권고되며 집중치료실 또는 뇌졸중전문병동에서 지속적으로 혈압을 모니터링하는 것이 필요하다[60]. 혈전제거술과 같은 재관류 시술을 받은 환자의 경우 특히 성공적인 재관류가 달성된 경우 최소한 시술 후 첫 24시간 동안 혈압을 180/105 mmHg 이하로 유지하는 것이 권고된다[60]. 혈전제거술과 같은 재관류 시술을 받지 않은 환자들에서는 급성 허혈뇌졸중 후 3일 이상 고혈압이 유지되는 경우 혈압 감소 약물을 처방하거나 재시작하는 방안이 권고된다[61-63].

급성기 이후 뇌졸중 재발을 예방하기 위한 최적의 혈압 목표는 여러 임상시험 및 메타 분석 연구 결과를 통해 수축기혈압 120-140 mmHg의 범위로 권고된다[64,65]. 선행 연구에서 수축기혈압 120 mmHg 미만인 경우 오히려 뇌졸중으로 인한 사망률이 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있어 이에 대한 주의가 필요하다[66]. 이러한 결과에도 불구하고 환자의 기능적 상태, 취약성, 인지기능 및 관련 질환을 고려하여 목표 혈압을 개인별로 결정하는 것이 필요하다. 일반적으로 주요 목표는 혈압을 140/80 mmHg 미만으로 감소시키는 것이며 환자의 임상적 상황상 가능한 경우 혹은 소혈관질환 또는 열공뇌경색의 병력을 가진 환자의 경우 혈압을 130/80 mmHg 이하로 유지하는 것을 목표로 한다[67,68].

2) 인지기능 저하와 고혈압

고혈압과 인지기능의 병리생리학적 연관 고리로는 뇌백질 변성, 미세출혈 및 열공뇌경색으로 이어지는 대뇌소혈관의 리모델링이 주요 기전으로 알려져 있다[69]. 중년기의 고혈압은 추후 발생하는 인지기능 저하 및 치매의 주요 아형인 알츠하이머치매 및 혈관치매와 연관성이 있다[70,71]. 최근의 28,000명의 환자를 대상으로 한 메타 분석 연구에 따르면 고혈압 치료를 통해 평균 수축기/확장기혈압을 10/4 mmHg 감소시키면 치매 발병 위험도가 13% 감소되는 것이 확인되었으며 수축기혈압 130 mmHg 이하로의 지속적 관리는 뇌백질 변성의 진행 및 전반적인 인지기능 저하를 줄인다는 보고가 있다. 따라서 인지기능 저하 및 치매의 위험을 줄이기 위해 중년기 및 노년기에 고혈압 치료를 시행하고 혈압 관리를 지속적으로 추구하는 것을 권장한다[72-74].

결 론

심뇌혈관질환의 위험을 줄이기 위한 노력의 일환으로 국내 환자들의 고혈압 치료율과 조절률을 더 높게 개선할 필요가 있으며 만성 질환 환자군을 접할 빈도가 높은 신경과 의사로서 정확한 혈압 측정, 위험도 평가를 통한 치료 결정 및 목표 혈압 수립, 각 계열의 고혈압 약제의 특성을 파악하고 부작용을 줄이기 위한 노력이 진료 일선에서 필요하다. 2023년 유럽고혈압학회 가이드라인의 내용이 고혈압의 분류, 목표 혈압 등의 측면에서 다소 복잡하게 보일 수 있으나 고혈압의 등급과 단계에 따른 위험군의 분류, 동반 질환과 환자의 상황에 맞는 개별적인 치료지침 등이 제시되어 있어 임상 현장에서 합리적으로 이용할 수 있을 것으로 생각된다.